|

New York Times, April

28, 2009

A High Freudian Love

Triangle With Three Sharp Points

By CHARLES ISHERWOOD

|

|

|

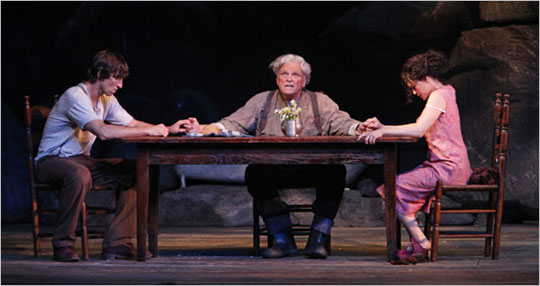

Pablo Schreiber, left, and Brian Dennehy play father and

son, and Carla Gugino the father’s new wife, in Robert

Falls’s production of O’Neill’s 1924 play "Desire Under the

Elms," at the St. James Theater. Sara

Krulwich/The New York Times |

A lust for sex and a lust for

real estate are familiar passions to many, notwithstanding the

plummeting co-op market and those libido-dampening Dow numbers. But

these primal drives take on an eerie, entrancing strangeness in the

gutsy revival of Eugene O’Neill’s “Desire Under the Elms” that

opened Monday night at the St. James Theater. Portraying a

stepmother and stepson doomed to enact a feverish, erotic dance that

will ultimately destroy them, Carla Gugino and Pablo Schreiber fight

like tigers in a cage over a legacy of land, even as their bodies

cleave violently together, aflame with urgent need.

First seen at the Goodman Theater in Chicago, where it was the

centerpiece of a winter festival devoted to O’Neill, this visually

spectacular production wraps his powerful but problematic 1924 play

in a big bear hug, making no attempt to throw a blanket of soft

naturalism over its sometimes glaring flaws. On the contrary, the

director Robert Falls, who led the last Broadway revival of “Long

Day’s Journey Into Night,” honors O’Neill’s ambition to transplant

Greek tragedy to American soil by mounting the play on an epic

scale, even adding a few expressionist touches of his own. (A

recording by Bob Dylan is unexpectedly heard.)

Do not bother to scan the sky-high rock piles of Walt Spangler’s set

for glimpses of the titular trees, however. Mr. Falls has eliminated

them, allowing the close, coddling maternal symbolism they are meant

to provide to go by the wayside. It is not much missed. “Desire

Under the Elms” dates from what might be called O’Neill’s High

Freudian phase, which would also include the trilogy “Mourning

Becomes Electra” (a modern-day retelling of Aeschylus’ “Oresteia”)

and “Strange Interlude,” a long evening’s journey into the tortured

heart of a neurotic named Nina.

Although the plot of “Desire” is drawn directly from Euripides’ “Hippolytus,”

and O’Neill played down Freud’s influence, the Oedipal instinct is

front and center in the psyche of the young Eben Cabot (Mr.

Schreiber), who still mourns his mother’s death and bitterly blames

his father, Ephraim (Brian Dennehy), for working her as hard as he

works himself and his three sons on their New England farm. (Boris

McGiver and Daniel Stewart Sherman play Eben’s brothers, loutish

brutes who abandon the farm to pursue gold rush dreams in

California.)

When Ephraim brings home a blushing rose of a new bride, Abbie (Ms.

Gugino), Eben is enraged at the potential loss of his inheritance,

until the hypnotic allure of his stepmother begins tearing down his

emotional defenses.

The process is enacted with captivating magnetism by these two

exciting actors. Rarely has sexual passion been depicted with such

tense, animalistic ferocity on a Broadway stage. After a somewhat

ponderous start, during which we have a little too much time to

marinate in the stagy, countrified dialect O’Neill employs, the

temperature rockets upward when Abbie and Eben meet and exchange a

long glare in the farmhouse kitchen. Mr. Schreiber, with a backwoods

face and beefcake body, radiates a febrile, simmering fury in a

performance of taut intensity. From beneath a dark fringe of hair,

Eben’s eyes glow with compulsion, recognizing in the

delicate-seeming Abbie a formidable competitor, and scorning her as

a “harlot” tarnishing the memory of his sacred mother.

|

|

|

|

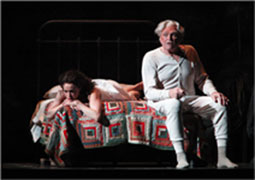

Carla Gugino and Pablo Schreiber in "Desire

Under the Elms." Sara Krulwich/The

New York Times

|

Carla Gugino and Brian Dennehy in "Desire Under the Elms."

Sara Krulwich/The New York Times |

Abbie’s approach is more

accommodating. She has learned the harsh compromises life demands

and made a cruel bargain by marrying the flinty, much older Ephraim.

In Eben, her rival for the home she has finally found, she also

instinctively sees a source of sexual and emotional consolation.

Embracing the florid extremes of the role with a thrilling bravado,

Ms. Gugino makes us see with painful clarity how these two

conflicting desires corrode Abbie’s psyche so completely that they

are finally blended into one consuming need to retain Eben’s love at

all cost. It is a brave, luminous, ultimately haunting performance.

As the ornery Ephraim, proud of his independence but secretly

longing for understanding, Mr. Dennehy has grown into the role since

the Chicago run. His craggy face resembles a worn rock in which time

and experience have etched hard lines, but Mr. Dennehy didn’t before

seem to possess in his bones the grim, flinty spirit of the man. He

does now, at least in fierce flashes. During the scene in which

Ephraim exults in his new fatherhood—taunting Eben with the loss of

his inheritance, unaware that his son has fathered Abbie’s child—Mr.

Dennehy exudes the hungry malice of a jackal tearing away at a

rodent.

“God’s hard, not easy,” Ephraim observes with a measure of

satisfaction. The same could be said for many a second-tier O’Neill

play. This great American playwright never shied from a dramatic

challenge, even if he sensed that his talents might not be equal to

the demands placed on them. His weaknesses are extravagantly

apparent in “Desire Under the Elms.” The writing can be repetitive

and painfully overexplicit, the attempts at poetry blunt and

strained. Rather than achieving the grand synthesis of tragedy and

humble domestic drama that O’Neill envisioned, the play sometimes

comes across as melodrama overblown to mythic proportions.

And yet O’Neill wrote with a deep understanding of the destructive

clash between the ferocity of human needs and the hard exigencies of

life, and held a deep belief in the power of drama to imbue human

experience—even the most sad or sordid—with a moving grandeur. With

Ms. Gugino, Mr. Schreiber and Mr. Dennehy giving performances of

unflagging commitment and exposed feeling, the production manages to

transcend the play’s flaws to transmit the penetrating truth of

O’Neill’s underlying vision, of the ineradicable human need to

possess and be possessed.

|