|

In an Hour of Spring

By Agnes Boulton

Illustrations by Thomas Fogarty

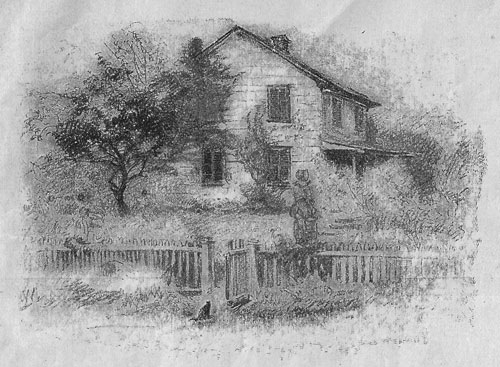

The whole house, like something from a fairy tale, seemed to suggest

beautiful and ideal old age. Youth it certainly never could remind

anyone of, with its quaintly wonderful old-time touches. Outside it was

small and neat and triangular, with tiny square windowpanes, through

which peeped Miss Faith’s rose geranium plant, with green slatted

shutters and its little particular path, running straight to the picket

gate. Inside it was quite as was Miss Faith herself – delicately

fragile, in a wistful old way. There were tidies of very fine

crochet-work, such as one does not see nowadays, on the backs of the

parlor chairs, to keep company with odd little ornaments and

funny-looking pictures of plump children and pale ladies. There was fine

furniture, heavy old mahogany, and delicate little spindle-leg pieces,

and a beautiful marble top, on which Miss Faith kept her very finest

china tea-set. Indeed, Miss Faith had held, by some magic, all the

beautiful part of a past century in her little house.

And by the same magic it seemed she had somehow caught securely the

charm of her own distant youth. Miss Faith had been a beauty once upon a

time, a delicate thing of wild-rose joy, of tender, exquisite grace. As

she entered the kitchen this wide-awake morning of May, and moved with

quiet steps about her duties, with her soft gray curls and gentle,

pathetic face, she seemed like a pleasant memory of long-ago times.

For, in truth, that was what a great part of Miss Faith was. All her

life was a memory. For a while it had been a memory and a hope. Then, as

the gentle, inevitable years went by, the little hope had died and been

buried with a few of Miss Faith’s tears somewhere in the garden of

dreams.

|

|

|

The Ladies' World,

April, 1912 |

|

Do you remember how, in the fairy tale, there was the beautiful

Prince, who came from a distant kingdom and rode his way straight into

the heart of the Princess? And how he goes away to wars and the Princess

remains at home to grow old and ugly in the midst of her tribulations?

And then how, one fine morning, the Prince rides home again to his

bride, and by the gift of the fairy Love they both become young and

beautiful again, and live out their days in joy?

Such was the fairy tale of Miss Faith’s life. Only in this revised

version the Prince had gone away and quite forgotten; probably, as Miss

Faith often reasoned, because he had never known. And though she, as did

the Princess in fairyland, lived her life true to her ideal, there would

be no coming of a gracious fairy in the end to change her gray hair to

gold again, and give her back the joys of life she had missed.

As Miss Faith, this fine May day, washed the breakfast dishes and set

them on the tray to drain, she gazed out above the white curtain to

where a whole exquisite mass of pink blossoms danced in the sunlight. A

faint desire woke in her to run out there madly, to bury herself in the

low-hanging boughs, to breathe in their fragrance and brush their soft

petals against her face. It was the fragrant call of spring, mocking

her.

She remembered that, after all, she was an old lady, with her chances of

mad riots among the apple-blooms far in the past. Methodically she

continued her work, raising each dish from the foamy suds as carefully

as if it had been some priceless bit of china.

After the dishes were done, and every detail of the small kitchen shone

in its usual orderliness, Miss Faith went out into her garden. Across

the fence the mischievous apple-trees still beckoned her. What knew they

of old age? But Miss Faith bent down above the border beds, and turned

the fresh damp earth over with a trowel. Later she was going to

transplant her geraniums there. After awhile, with the May sun warming

her back, and the May breeze flirting airily with her checked apron, she

pottered away among the garden duties. The spring air roused in her a

sudden enthusiasm for work. Then fatigue overtook her, and she left her

gardening and sat upon the porch steps.

As she sat there a hundred little memories came out of the spring

warmth, and flickered through her heart. After awhile she got up and

went into the house. From the little cupboard built over the end of the

mantelpiece she brought out two objects. With half a sigh she went out

again on the porch steps, putting them in her lap.

One of these things that Miss Faith had kept for something like forty

years in the end cupboard was a man’s worn leather glove. The other was

a much-rusted fishing-reel. For awhile she sat still in the sunlight,

just looking at them. Then she put her faded little hand into the great

glove. A slight moisture gathered in her eyes.

Then a half-ashamed, half-wistful smile crept over her face.

“The idea – little fool!” she said through her smiles and tears.

And as she had said it, as she smiled and wiped the tears from her eyes

with the back of her hand, steps came crunching up the gravel walk.

‘Twas but the work of a second for the little lady to whip the corner of

the apron over her lap. A man, possibly a tramp, was coming toward her,

his cap held in hand.

But Miss Faith was not afraid – too many tramps had she fed and sent on

their way in the spring and fall of the year.

“Good-morning,” she said. “What did you want?”

The man hesitated; his blue eyes, a bit faded, looked from Miss Faith to

the trim-shuttered windows, from which peeked the rose geranium. She, in

that little moment, watched him and had to change her opinion; he was no

tramp, he was too neat and carried himself too well. True, his shoes

bore the mud of country roads, but they were strong boots and well-made.

“May I be asking a bit of bread of you, M’am?” said he. His voice had a

quaint touch of brogue that carried above the hoarseness. “I’ve traveled

far this morning, and tired I am, with the mud of springtime on my

boots.”

Miss Faith arose, holding together the corners of her apron. For good

reasons she had always held a soft heart towards those with the Irish

turn to their speech.

“Come up to the house,” she said, in her slim old voice. She led the way

there and took the man into the kitchen with her, to sit by the table,

while she cut big slices of bread and filled them up with cold meat. As

she prepared these the man followed her with his eyes, as if he were

full of talk, and only waiting a willing word on her part to bring it

out.

“If you want to wait,” she suggested, “I will make you a cupful of hot

coffee.”

This was an unusual thing for Miss Faith. But perhaps the combination

was the unusual type of caller and the May day, which roused in her the

instinctive passion of womanhood to help weary hearts along their upward

climbing.

So she laid before him a meal that filled his eyes with gratification.

And Miss faith, being somewhat lonely, let him talk to her; and as he

talked, and his blue eyes twinkled and shone as he told of things that

had happened to him in the past week, the finger of memory began to poke

among the cobwebs in Miss Faith’s heart, and rouse in her a dim and

incomprehensible feeling.

Then, as he drank the last of his coffee, he turned the conversation

from himself to questioning. Did she remember a young girl that had

lived here years ago – a Miss Allen?

Miss Faith’s heart gave her the peculiar sensation of having been

suddenly clasped by a cold, wet hand. The incomprehensibility cleared.

She – was not she Faith Allen, the old-time beauty? And he – this faded

gallant of the road – he was Barney Connor, of long-ago.

“I knew a Miss Allen, yes,” the little lady answered stiffly, because

she was shocked into stiffness.

“Ah, she was the beauty,” he praised. “With the lingering of the roses

in her cheeks an’ the shyness of the wild deer itself in her two brown

eyes. A fine girl.”

He looked past Miss Faith through the open door with a strangely tired

and wistful expression.

“It’s old now she is, if alive at all, and with grown children, no

doubt.”

She stared at him silently. A tiny topaz-eyed cat entered from the

garden and began to purr in a staccato treble. From outside the faint

smell of the apple-blossoms reached them.

“But I’m thinkin’ of her yet,” the old man murmured on, “deep in my

heart, as she was then – without the husband she’s been havin’ and the

children she’s been raising.”

In Miss Faith’s mind, too, was a memory. The tragedy of age seemed very

bitter. The many long twilights she had spent alone returned to her, and

the empty hours of her later life.

“Did you know her well?” she asked.

The man smiled at her.

“Not so well,” he replied. “I was visiting here, an’ met her like that.

She took my heart of a sudden, and made up my mind to ask her opinion on

the subject when a little friend of hers told me she was in love with

someone else. I knew she was shy like, an’ never lifted her two eyes to

mine. So I said nothing of it and went back to the old country with my

uncle.”

“Maggie Havens!” exclaimed the little woman dismally. “Dead twenty years

now.”

He stared at her for this; stared for a long time it seemed to them

both. Then he said slowly, as a man who makes a statement:

“You are Faith.”

She laughed almost hysterically.

“I’m Faith,” she said, and her voice sounded almost hard. “And I’ve been

loving the picture I held of you in my heart for forty years. I got in

love with you then, Barney, an’ because the Lord made me that way I’ve

loved you ever since, Barney Connor. It’s been a washed-out sort of

love, I guess, living on shadows – but I wish now you had stayed away,

because I’ve nothing” – she paused – “not even the shadows of company

now.”

She got up and began piling his dished together mechanically.

“Men are different,” said he. “I’ll not lie to you now, as I might be

doing, swearing I never for a moment forgot you. Men are different – an’

love’s not the great thing with them, I’m thinking; it stays forever in

the hearts of women. I’ve lived a hard life, and though I’ve made

friends with many, I’ve been a lonely man. I never married, as perhaps

you may be guessing. And in my loneliest times, when the ache for a home

was hard on me, and the ways of the world seemed weary to my feet, I’d

think of you with a pain in my heart. Other women did not attract me,

somehow. And when I got caught in danger, and life was looking doubtful,

in those moments I thought of you, too.”

Miss Faith took the dishes to the sink. The man stood lingering in the

door.

“I’m not so young as I once was, but I’m a good man yet, and I’ve got

some money put by. Miss Faith, will you take me as I am, and marry me?”

Miss Faith turned to him. She spoke gently, with a sad firmness.

“Barney, we’re too old, both of us. It is no use thinking of it. Ten

years ago, maybe… But I had given up ever thinking you’d come long ago.

We’d marry, and then somehow it seems to me we’d always be thinking of

each other as we’ve thought all these years – young and without the

wrinkles. I’ve thought it over while you was talking, and I’ve decided.

You come here unknowing an’ I want you to go as you come.”

“I” – the man’s eyes filled slowly and he spoke with a simple dignity –

“I was forgetting that I am old. I don’t blame you for not wanting me,

Miss Faith. And don’t you go bothering about it. Good-bye.”

He went slowly down the path. All the debonair manner of his coming had

left him. He looked like an old man now, with lagging steps and the

straightness gone from his shoulders.

Miss Faith watched him against her will. Each step he took seemed to

bind her more helplessly to a dim and lonely future. Strangely enough,

she thought not of him now, on whom her thoughts had been dwelling for

so long a time – not of him, but of herself. She saw her life as it had

been; she saw the long and lonely evenings that were to come; she saw

herself rising day after day, to prepare her lonely breakfast. She

thought of it all, and her heart felt that dull ache that meant love to

her.

And then there came to her the memory of the things she had been able to

enjoy because this love had made her clear-eyed, had raised her above

the grubby things of life to a splendid realization. The lingering,

fading sunsets, the beauty of the cedar trees, darkly outlined against

the glowing sky; the still freshness of the dawn, when the day breeze

first gently moves among the branches; the moist, chill glory of moonlit

evenings in the fall, when white mists rose from the ground and spread

across the fields; the splendor of the rushing northeaster, the mystery

in the many moods of the ocean, that beat a mile from her door – all

these things had been hers, and in spirit she had shared them with him.

For a moment she hesitated. Then, with little fluttering, flying steps,

she went down the path after him. And from the orchard the dancing

blossoms mocked at her.

He turned to her in wonderment.

“I guess we’d better try it, Barney,” she said in a shaken voice.

“You’ve made the world a beautiful place for me. An’ it’s hard that when

we’ve wanted each other a lifetime we shouldn’t be companions in our old

age. It’s been a long time waiting.” The Ladies' World,

April, 1912. |