|

Chapter XIII

At a time just before the Great Depression in 1931,

Agnes was living with the two children, Shane and Oona in The Old House

in West Point Pleasant, New Jersey. My mother Budgie, Nanna, little

Robert and I were living in the Merryall house, north of New Milford,

Connecticut. Robert was Margery's second child and born in July 1930.

My earliest memories of the Merryall house were when I

was about four years old. Set back from a dirt road and edged with

several huge old maple trees, the two-story Colonial was painted a soft

barn red, with a side porch facing the valley below the New Milford

hills and looking down on the Aspetuck River.

The peach tree in the side yard was the largest one in

the whole world, with more peaches hanging from its branches than anyone

could imagine. So we believed. Inside the old house, a large living room

boasted a great stone fireplace around which the family had tea each day

in the late afternoon. It was here, in this beloved old house, where my

family and I spent our summers.

Six months before Robert's birth, Margery married Louis

Colman, who became a father to us both. I loved him dearly, but after

about a year and a half he left and went away to New York City. It broke

my heart! Budgie told me later, when I was grown, that she wanted to

raise her children alone because she wanted sole control over how they

were to be raised. For all my mother’s wild youth, she was very rigid in

her ways during our childhood, mellowing greatly in her later years.

Only a baby, Robert was not good company for me at age

four, and most of the other people around were grown-ups. So I had to

entertain myself with the attention of friends and relatives who came to

visit. My very favorite was Marnie, my mother’s Aunt Margery. We

pronounced her name "Mahnie," the English way. (Many years later I named

my first child Marnie.) I also loved to see Marnie’s husband, Uncle

Francesco Bianco. He wrote poetry and had a bookstore near Washington

Square in New York City. In the summers they left the city and came up

to Merryall to stay in their charming storybook house up the hill from

us on Frenchman's Road.

Aunt Marnie was tall and thin, with her hair done in

what was called a Dutch boy coiffure. We called it simply “a bob!”

Marnie had a gentle, caring way about her and seemed to see all through

kind eyes. She delighted us with her wonderful wit, enhanced by the

British accent she managed to retain through all her years. I adored

her. Uncle Francesco was a small kindly man with graying reddish hair,

and his light blue eyes crinkled up at the corners when he told his

wonderfully funny stories.

We would often all troop up the hill to visit the

Biancos in their comfortable little home. The gray painted cottage wore

solid light blue shutters with quarter moons cut into them. On the side

of the house there was a huge wooden rain cistern where the rainwater

was collected for washing. We had to push open the small gate as we went

into the yard and Aunt Marnie and Uncle Francesco would call a cheery

greeting from the house, “Come in! Come in!”

Aunt Marnie some days found interesting things for us to

do, and often told us stories about animals she had known, such as a

baby alligator she kept warm on cold nights by wrapping him in a piece

of flannel and taking him into bed with her, or the cat who insisted on

finding mice for my brother and me whenever we cried.

We loved her stories and her story books. One day Aunt

Marnie took us for a walk in the woods behind her house. Running

alongside on his short little legs, her small black dog named Scottie

went with us. This time we found an ant hill about two feet high, the

likes of which I have never seen since. We stood amazed, watching the

ants climbing up and down the hill. Scottie wanted to explore the

mountain and tried digging into it with his fast little paws. Marnie

distracted him with a stick to chase.

On the way back to the cottage, Marnie told us we would

find Uncle Francesco making spaghetti. It was intriguing to see him

cutting rolls of dough into thin strips and then hanging them over a rod

to dry. By dinner time he would have made a delicious sauce with

tomatoes and vegetables from the garden, and also baked a loaf of thick,

crusty bread. The smells of all the good food were overwhelming, and we

were delighted to be invited to stay for dinner. Marnie was very proud

of her garden and told us the names of the various vegetables and the

glorious flowers. These were special memories to tuck away for later

years.

In those early days, Barbara spent several summers with

us. We missed her so much in the two winters when she had to go away to

boarding school. Her mother, our Aunt Aggie, was very busy with travels

and writing and needed help with Cookie’s care.

|

|

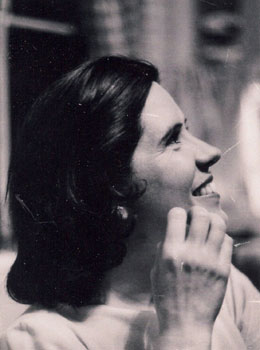

| Young Agnes

with baby Barbara Burton, circa 1914-1915. |

Barbara

Burton Davis, 1935.

(She added the name Davis in NY.) |

I recall one summer when Barbara was about seventeen and

staying with us, she came down with pneumonia. There was an air of worry

as Nanna nursed her back to health and I remember her looking so pale

and fragile lying on the large bed in the upstairs North Room. I was

afraid she might die. She seemed like an adult because I was thirteen

years younger. She was sweet and gentle and the family loved her. As I

remember her in those days, she was very beautiful with large, wide-set

dark brown eyes and a lovely smile. We needed to be as quiet as possible

so Barbara could rest and be well again. Nanna wrote to Aggie telling

her Dr. Stevens came to see Barbara and ordered lots of fluids. In time,

her fever came down and she recovered slowly. It was good to see her up

and about once more as her energy returned.

Barbara told me later of the time when she stayed with

us all one winter and went to school in New Preston, and how the other

children teased her and threw cow manure at her because she was a “city

girl.” It was painful for her, but she was very philosophical about it.

Barbara had learned to hide her hurts well.

|

|

| Barbara and

Shane, 1920. |

Barbara

Burton, 1932. |

As I recall the Merryall summers, I think of lines from

a favorite song called “The Old Oaken Bucket” that Nanna sang as she

played the piano. “How dear to this heart are the scenes of my

childhood...” For me at age five, Merryall and the scenes of my

childhood became a wonderful children’s world. The second summer I

remember was filled with good times, cousins coming to visit and the

usual grown-ups who came and went. We picked and ate rosy-ripe peaches,

watched the little goats in the shed down the hill, walked through the

high wild grasses that grew far behind the house and down to the river

below, and we played children’s games.

Oona came to stay with us that summer when she was

seven. Two years older and a little taller than I, she was like my big

sister. Nanna told her that the warm, dark tan she had acquired made her

look “as brown as a berry.” Oona had a crown of thick brown hair, intent

wide-set eyes like Barbara's, and a winning smile. She cast a spell over

me in those early years and I agreed to do whatever she told me.

One sunny afternoon, Oona had an idea. There was a large

stone wall around the well in our front yard, and the water bucket hung

from a sturdy ring attached to a rope for hauling up our drinking water.

When Budgie and Nanna were indoors, Oona suggested,

“Let’s put our dolls in the bucket by the well. We can send them down

into the water to have a bath.” It sounded like a fun idea to me, so we

proceeded to do just that, cranking the handle that lowered the bucket

and the dolls down into the well. After a splash sounded, we knew the

dolls had gone into the water. Oona cranked them up again. Our babies

were drenched!

It took days for the cloth bodies of the dolls to dry

out, and as they lay in the sun their composition faces became awfully

cracked. So much for doll baths in the well. We also had a “talking to”

from Nanna, but she took pity on us as we nursed them tenderly until

they were thoroughly dry. They were definitely not so smooth anymore.

“Let’s make believe they have a dreadful disease,” Oona

suggested, and we amused ourselves with that idea for awhile. I found my

doll in an old treasure trunk years later, but she had never recovered

from her dunking!

The old house still stands in Merryall, and sometimes as I drove by

many, many years later, I liked to think of the happy times we spent in

that magic place, with all the family, including Oona, Robert, the

Woodville cousins and our beloved adult friends who paid us so much

attention.

Our winters had been spent in the studio-bungalow, which

my grandfather Teddy had owned in Woodville. There was a hand pump in

the kitchen for water, a kerosene lamp on our table, the large tin tub

for baths, and a wood stove for heat. Our toilet was outdoors and called

the “back-house” or the “out-house.” It was during the Great Depression

and we grew an enormous garden; at least it seemed enormous when the

family weeded it each week. After a harvest in the autumn, Nanna and my

mother stored beets and carrots in barrels of sand in the cellar and put

up many jars of fruits

and vegetables.

Mother bought a small red and white cow we named Daisy

and she learned to milk her. She told me years later not ever to tie

myself down learning to milk a cow! We had chickens, which my

grandmother tended and sometimes killed so we might have a chicken

dinner. I refused to eat them. I knew what had happened to them when I

heard them screaming as Nanna chased them to end their days on the

chopping block.

Nanna made hooked rugs and sold them so we were able to

buy large mail-order sacks of flour and grains for breakfast cereal and

bread. Mother drove us down in great style to the New Preston train

depot to pick up those bulky supplies. She had an old eight-passenger

navy blue Buick convertible, with running boards on each side, and

Robert and I were allowed to sit in the small pull-up seats in the back.

Aunt Bobby and Uncle Walter lived up the hill in a

handsome cream-colored Colonial farmhouse surrounded with great maple,

oak and horse chestnut trees. The huge old horse chestnuts were our

favorites because they dropped satin-skinned nuts down for us to use in

all kinds of games. The small red barn down across the field, housed one

cow for milk and several horses for riding. The barn extension held

many chickens and a feisty rooster, while cats and dogs joined the

outdoor scene and followed us all around. Oona, and sometimes Shane,

would come up to visit and were warmly included in this family with six

children, and my brother and me.

We shared summer swims in a favorite place. Barefoot,

we’d hike up the dirt road and down a grassy path to the wide, cool

brook, where a high waterfall pouring down on us was the most fun of

all.

As children we didn’t really feel the impact of the

depression, but I do remember my Uncle Walter sitting on the running

board of his car and weeping, with his head in his hands, because there

was no work for him anywhere. I was very touched by his distress,

realizing in a child’s way how serious it was. I have never forgotten

the feelings.

Chapter XIV

Chapter XIV |