|

Chapter XV

Five and a half years younger than Shane, Oona blossomed

when she had his company. They must have felt close in their pain, and

the quiet support they gave each other may have eased the ache of

abandonment they both suffered for so long. Oona was excited to have

Shane around whenever he came home to The Old House for his summer

vacations. He seemed very special to her, and generally kind and

big-brotherly to us both.

We loved going to the beach with Shane, where we could

spend the day at Jenkinson's Pavilion and the connected pool. I hadn’t

really known Shane much before and I grew to love him. This handsome

young cousin of mine was tall, slender and always very tan. He looked so

much like his illustrious father, with wide-set, dark brown eyes and a

high forehead. He had a kind of shy, lop-sided grin that always appealed

to me. I loved hearing him talk to us in his special quiet, soft voice.

|

|

Budgie with Dallas and Oona in

Jersey. |

|

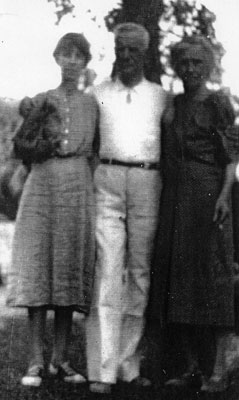

Jimmy,

Agnes, Shane and Oona with Middie dog. |

|

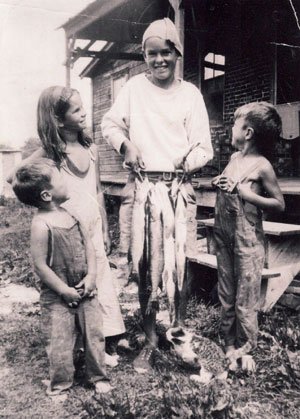

Shane with

his prize catch, with Oona and two unknown admiring boys. |

Jenkinson’s Pavilion, on the Point Pleasant beach,

became a real hangout for us every summer, as well as at times in the

spring and fall. It was a big part of our lives, and we would amble

along the boardwalk eating popcorn or ice cream, maybe stopping at the

Arcade to see who might be there that we knew. My favorite thing was

savoring the Italian ices and I still remember my favorite flavors,

honeydew and watermelon. There were times when I became distressed as Oona would take one bite from a cone, then throw it away, or buy a big

bag of popcorn, eat a little and toss the rest in the trash bin. Coming

from a home where every penny counted and they were hard to come by, I

couldn’t bear to see her do this. I wanted her to ask me if I would like

to take them home before she tossed them. I had been a child of the

Great Depression and later realized it had affected me. Oona and Shane’s mother and

father certainly had fewer financial worries during that time and the

children did not appear to be aware of such things.

Oona and I spent a great deal of time roller skating and

going to the boardwalk by the beach where skating down a large bumpy

ramp was the most fun of all. The wide ramp, made of heavy boards,

slanted from the boardwalk down to the sidewalk. It thrilled us to roll

down with the skates going clickety-clack all the way, with the hope

we'd be able to keep our balance as the ramp turned from wood to

concrete. We got a few bruised knees but it was worth the delight!

When Oona and I joined the Girl Scouts, the Pavilion

again became a special place. As Scouts we were learning the Morse Code

and how to tie knots of all kinds in the large school gymnasium, but

each Monday night we would go with our scout leaders down to the

boardwalk where Sammy Kaye and his orchestra took time from their

evening entertainment to play for us. They played for the Scouts for an

hour and a half, and we loved it as we learned to dance and “jitterbug.”

“Swing and Sway with Sammy Kaye” was the highlight of our scouting days.

Jenkinson’s Pavilion was where Sammy Kaye had his start, and we were

most excited when we heard him later on recordings over the radio.

Early one summer, Oona chose to buy a new rubber bathing

suit as it was the latest rage and quite stylish. We swam and played in

the pool at Jenkinson’s, when suddenly Oona backed up against the side.

She was very upset and called over, “Dallas, go get my big towel in the

bath house…quickly, please…!” This modern creation had split right up

the back!

The summers were full and we shared good times. Often on

the ride home from the beach, Shane would stop at the drugstore and

treat us to a Black Cow — root beer with vanilla ice cream. At the end

of the summer season it was difficult for Oona to see her brother leave

and go back to boarding school. Another abandonment. It must have been

equally as hard for Shane to leave and see Oona staying at home with

their mother.

In the fall of 1936, Agnes announced her plans to be away

from home for the entire winter, going to California and unable to take Oona with her. She rented a house in Key West, Florida, asking Budgie

and Nanna if they would take the family, along with Oona, down for the

school year. As part of the adventure, we were to travel south on the

train. The school principal talked to the family and suggested we go to

a parochial school in Florida, because the public schools in the south

were academically far behind the northern schools.

The train was exciting for Oona, Robert and me. I recall

a rather unusual snowstorm in Georgia as we went through, with another

strange memory being the dreadful taste of sulfur in the water on that

part of the trip. We could not bear drinking the water and made horrible

noises to show our dislike.

One other very disturbing thing on that part of our trip

were the chain gangs that we saw from the train as we traveled though

the deep South. Clad in black and white striped uniforms the prisoners

worked on the roadsides, chained to each other by shackles around their

ankles. The guards appeared big and ugly with rifles over their

shoulders. Budgie explained the scene and gave us a long remembered

lesson in prejudice and cruelty. Years later in teaching history through

music, I was able to relate this first hand to my students while using

traditional chain gang songs.

The bridge to Key West had been washed away in a severe

hurricane the year before and we traveled to the island on a ferryboat.

Once settled into the house on South Street, we found ourselves in a

neighborhood with lots of boys who came out of the woodwork when two

girls appeared on the scene. Oona and I were delighted, and my mother

dismayed, when a knock at the door produced a large box of paper hearts

cut from newspapers. Then we heard young voices outside the back

window singing songs in Spanish and calling out a word that sounded

like “Calinda.” Budgie said, “Do not ask

anyone what it means...it might be rude.” Of course we asked about it,

and found that our young admirers had been calling us “pretty.”

|

|

Key West, Florida, the house

on South Street, circa 1936-1937. |

|

Dallas and

Oona. |

The sunny days in Key West were filled with good times.

We roller-skated on the sidewalks and Oona taught me how to ride a

bicycle. We spent happy hours swimming in turquoise water on a long

beach down the way from the Hemmingway house. Robert had found a friend

in an old man next door who took him out on his fishing boat almost

daily. The “Old Man” and his wife lived right next to us and they were

like treasured grandparents to a little boy who needed not only a father

figure but also good friends in his life.

|

|

|

Key West

Winter, Robert, Dallas and Oona, circa 1936-1937. |

|

|

|

Dallas and

Oona. |

Soon came the season when small purple and gray stone

crabs covered the beach. Oona and I gathered up a dozen or so and put

them gingerly into a can we found. At home we divided them up into two

small cans so we each had a little “family.” We tied long strings around

two of the less fortunate creatures, so they became our “puppy-crabs”

while we followed them around the living room on their leashes. At night

they went back into the cans with screens on top, but by morning all had

escaped. For weeks Budgie and Nanna were finding stone crabs — dead and

alive — behind the couch, under the chairs and wherever they could hide.

Budgie made us return the live ones to the beach. So much for the poor

little critters. Could they ever forgive us?

At the convent where we attended school, Oona and I went

early each morning to wait outside the gates before classes began. We

hoped to have a quick look at a handsome young choirboy whose name we

had learned was Lewis. I doubt Lewis even knew that we existed, but it

was fun for us to dream about him at such tender ages. The nuns, dressed

in full habit, were strict but very loving. Sister Annette, who taught

me in fourth grade, cracked me across the knuckles with a ruler if I

persisted in talking with my neighbor, which happened quite often. For

some reason I still loved her and knew she wasn’t being cruel. Oona must

have been less chatty in class — she didn’t seem to have that problem.

When spring came and school was over, we headed back to New Jersey. Agnes

had returned from California and Shane was arriving home from boarding

school. Oona was happy to be home with her mother and Shane — the family

who came and went in her life. Looking back, I believe Oona often took

advantage of the two years between us to exert some control over me,

which may have helped in her frustration of having no control over an

abandoning family. She was able to direct me and I was always there, as

were Nanna and Budgie. The three of us were perhaps the only dependable

people in the life of this little girl who so desperately needed a

reliable and “always-there” family. But they were not her very own.

We had happily returned to the ochre house next door to

the O’Neills. Though having enjoyed our stay in Key West, it was good to

be home and see our old school friends. One late afternoon Robert and I

were playing table games when Nanna came in to tell us to come outside

and see the huge dirigible that was going over the house. She told us it

was the Hindenberg from Germany. It was very exciting to see it at such

close range. Nanna said it was coming down low because it would land

nearby in Lakehurst.

We went back in the house to finish our game in the

dining room. Suddenly we heard Nanna cry out, “Oh, no! Oh, no!” We raced

into the living room to see what had happened. The radio news reporter

was telling us the Hindenberg had just gone down in flames over

Lakehurst, and they were trying to get everyone off. It sounded like a

nightmare! Oona had also heard about it and came over from next door to

tell us the sad news. We all sat with Nanna and Budgie listening to the

grisly reports. It was hard to believe we had seen it just a short while

before, floating up there in the sky above us, when it had appeared so

quiet and peaceful. This was May 1937.

Our family had many relatives from New York who often

came down on weekends. They were not Boultons, but were a big part of

our lives and very interesting people. Once Uncle Owen Williams, Nanna’s

brother from the mid-west, came with his four children to visit. Marnie

took the train down from New York and joined us. We had a jolly and

memorable time, going to the beach and playing games.

|

|

| Cecil

Boulton (right) with brother, Owen Williams and sister,

Margery Williams Bianco, 1940. |

Margery and

Francesco Bianco with Suzie dog, 1940. |

|

|

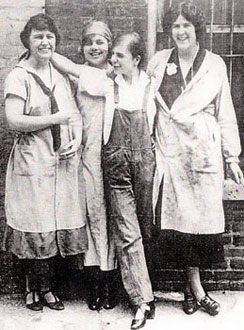

| Cousin

Pamela Bianco and Budgie. |

Pamela

(center), news clip with friends. |

Other relatives we really loved to see were Marnie and

Francesco’s grown daughter, Pamela Bianco. She was an artist and also

lived in the city. Oona would come over from The Old House and join in

the fun. Pamela always made us laugh with her antics and wonderful

British accent she would never lose. One evening she told us about her

new underwear with roses on them, and then proceeded to jump up, hoist

up her skirts and dance about the room with her new underwear well

displayed and singing about it with a marvelous British accent!

At the age of twelve, Pamela had been a child prodigy

with an exhibit of her artwork at the Leicester Galleries in London,

England. Walter de la Mare, the poet, saw her drawings and wrote a

series of poems to compliment them, all becoming a precious book called

Flora. The writer Richard Hughes called Pamela “that wonderful

painting child.” She grew up continuing her fine art work and

illustrating many books, including her mother's story of The Skin

Horse, which was our favorite.

When I was eleven and Oona was thirteen, we attended the

same junior high school in West Point Pleasant, but were two grades

apart. After school we spent time together, going to the beach and

“hanging out” in good weather, or going to the Point Pleasant Pharmacy

and meeting our friends, Mavis and Amada, and sometimes a girl named

Faith Springer. Sitting in the high old-fashioned booths we usually

ordered our favorite drink, a cherry coke with vanilla ice cream.

Oona loved giving boy-girl parties in The Old House and

I was always included. We danced to records on the phonograph, and

sometimes, without our parents knowing, we would play spin-the-bottle.

Very daring and so young!

The year of 1939 I was twelve and had become quite

aware of my mother and grandmother being very concerned about the news.

They were both avidly political and Nanna seemed to take great pride in

declaring herself a socialist. Robert and I had to be very quiet each

evening when the adults listened intently to the radio with Boake Carter

and Lowell Thomas reporting the news of the day. I remember their

concern over many of the stories that came through and stories which

stayed with me.

Budgie loved to listen to Marion Anderson and told us

much of what she knew about her life. The Daughters of the American

Revolution (D.A.R.) would not allow her to sing at Constitution Hall

because she was dark skinned. Budgie pointed out that this was another example

of racial prejudice. I also recall how furious Nanna was when Henry Ford, with his auto engineering, had been given a medal by the Nazi regime.

Then Charles Lindbergh, who flew across the Atlantic in 1927, received a

medal from Hitler! Mother told us all about the Nazis and Hitler in

Germany, and the family listened to much of the news about the war in

Europe and in Russia. When I shared some of these stories with Oona, she

didn't seem interested and did not care to talk about them.

Oona graduated from eighth grade at West Point Pleasant

and I went with the

family to her graduation. I was feeling awfully sad because it meant I

was losing her in the fall. In September she would go to a boarding school called

Warrenton Country School in Kentucky, and so far, far away! She was home

in New Jersey for the summer and Shane came home from school for his

annual visits. This was our last summer vacation in New Jersey, and we

made it a special time together.

Autumn came all too soon and Oona and Shane left. There

was a big empty space

in my life. When would she come back to The Old House again? Somehow I

knew

things would never be the same.

After that, aside from our summer vacations, I didn’t

see Oona much at all. I kept track of her after she left Warrenton

Country School in Kentucky and moved to New York City with her mother. A

decision was made to have her go to Brearly, a finishing school for

wealthy young women, and after entering school at Brearly, she became

“Debutante of the Year.” It was 1942. She was in another world and I

missed her terribly. She had been such an important part of my life.

The family was excited when two years later in 1944 Agnes had finished her book, The Road Is Before Us. An excellent

book review appeared in the Herald Tribune book section. Margery saved

the clipping.

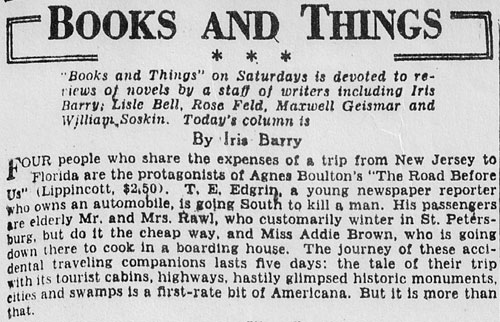

|

Book review

of Agnes Boulton's The Road Is Before Us,

Herald Tribune, October 21, 1944. |

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVI |